230822 Yohji Yamamoto

> words

The ability for a textile to incorporate time, ageing, wear, and use all of these to enhance the garment throughout its history gives each item its exclusivity and longevity. Dyes fade over numerous washes, or bleach out under sunlight chronicling the wearer’s usage, each fold records its own rate or usage and through this exposure each garment reveals its own time map. This ageless quality of Yohji Yamamoto’s clothes along with the black aesthetic became the designer’s uniform throughout the 1990’s. With time the black aesthetic became less important and the ageless and more subtle qualities of Yohji’s clothes became more endearing. Ageless and classic are often the same term within design vocabulary.

Yohji Yamamoto’s interest in textiles is the basis of much of his work, within his designs he can give them strength and fragility to form. Whether a garment is hemmed or not hemmed, allowed to fall on the bias or is gathered and tied, the textile embodies the wearer and is imprinted over time through use, unique to the wearer. The textile in this way does not wear out or become redundant but instead becomes enriched and personalised. The clothes are styled in such a way that they evade fashion and seek to avoid the disposable churn incorporated into the two shows per season ethos. It is possible to wear an early 1990’s Yohji garment with a contemporary piece of today 2022 without it either looking out of place or dated.

It needs to be remembered that when Yohji made his Paris debut in 1981, Paris was still promoting the “Jolie Madame’ candy-coloured expensive outfits, designed to be the envy of other women and pleasing to men. Yamamoto’s show, a parade of marching women, often shaven headed, in dark, distressed, asymmetric, oversized outfits confronted this preconception. Those that wore Yamamoto were labelled ‘the crows’. Paris was forced to reassess it’s preconceptions of female beauty. Yohji describes Winter as his favourite season and that he is a coat designer, “coats represent the house, protection” you can live inside protected. Yamamoto dresses women in men’s clothes, to create coats for protection. To protect women in men’s coats, empower the working independent woman. Soon after, in 1984, Yamamoto introduced his men’s collections to Paris with a similar aesthetic, not only were these pieces gender neutral, but many items were also interchangeable across the collections women’s to men’s. Yamamoto wanted his clothes to envelope a person’s body as opposed to exposing it. He describes the desire to design clothes that protect, hiding the body, protecting it from the elements, protecting it visually, this he says is about sexuality, gender protection. Yamamoto also wished to protect the clothes from fashion. His clothes are designed for long life, ten years or more, they are clothes designed to be outside of the fashion world or the perpetual transience of fashion. Yamamoto saw fashion design as too busy, fiddled with, appliqued, whereas longevity required simplicity and simplicity requires purity or essence.

The ‘Jolie Madame’ clothes of the eighties which were fitted, Yohji’s garments rarely fit or are fitted, hanging slightly oversize incorporating a space between the garment and the body allowing the wearer to inhabit the garment naturally. The garments are not tailored to the point that they dictate the way one sits, walks or stands and as such are not tailored for that moment, that fad, that season. They fall in soft folds, can be layered and as such absorb the texture of woollens, rough cloth, cottons, working together to create a timeless look of the chique vagabond. This volume, the space between garment and wearer animates movement, as the garments are rarely static, the recurring fall of soft fold over fold, a daily choreography, the unseen performance. The non-fit or non-fitted avoids gender stereotypes, it is gender neutral, non-ageist, non-sexist, androgenous. In 1998 Yamamoto presented an entire Menswear Collection on women, in 2004 a menswear collection with each male model skirted. Menswear and women’s wear collections consisting of garments, large loose-fitting garments, often asymmetrically constructed with minimal decoration, regularly with unfinished seams and nearly always predominantly black can be interchanged, traded between male and female.

Yamamoto’s clothes are often asymmetrical. Asymmetry falls within the broader philosophy of perfection and imperfection, unfinished. Like an artist’s sketch that allows the viewer to complete the composition, here the wearer completes the look by adding their personality. Symmetry, what the eye expects to perceive, is too easy, too ordered whereas asymmetry enhances the fall of a moving garment, a garment where space between the wearer and the clothing allow for movement. Clothes are never still, never perfect as drawn or as worn on the mannequin. One can imagine a symmetrical front, a symmetrical back but how often is anyone viewed perfectly square on, most of the time we are at three quarters view and moving, a composition which explores the rhythm of that movement not the static idealised perfection of symmetry. Asymmetry with sleeves of different lengths, pockets orphaned, panels opposed in both length, cut and volume enhance this continually changing moving composition. There is a romanticism to the clothing and a reference to the period of Romanticism. The clothes draw from the past yet embrace the degradation of the contemporary, their conclusion a timeless artifact outside of the seasonal à la mode procedures and practices, with gender-ambiguous clothing and reconstructions of historical western dress. As a musician or a dancer that continually practices scales or steps, Yohji has been described as a master tailor but he is this only in his ability to understand full traditional clothes and then to deconstruct and reconstruct them for the contemporary urban world. He understands that the same clothes worn on the catwalk by a model become knowingly reconfigured when worn by the customer, the designer no longer controls either their look or their composition. The loose fit, asymmetrical folded compositions, multiple layered items allow for endless re-composition controlled by the inherent theme of the quixotic itinerant gypsy. From his first men’s collection in 1984, Yamamoto had an objective to be the outsider of men’s suits, the outsider of the businessman, the desire to design for the urban vagabond. Within this parameter, material comes to life with time, making its mark over the years as it wears and frays, folds and creases, slowly incorporating the imprint of the wearer bearing the traces of a rich past. To encourage this Yamamoto can often manipulates his materials, crushing, boiling, fraying, cutting, crumpling, tearing or stretching it, so that it looks worked, lived in. Simple woollens, cottons, canvas, workwear fabrics, these are the materials that can absorb time. The unstitched pinstripe suit with hanging cotton threads seen also as a theme in the collections of Vivienne Westwood’s. Yamamoto’s clothes can get dirty, they can wear out and with that they barely age this only adds to the aesthetic.

Like all individuals practising outside what is expected this can create tensions between business and the business of design. Yohji’s company filed for bankruptcy in 2009 and was taken over by Japan’s Integral Corporation. We live in a world dominated by corporations and conglomerates, and these have their use as now Yohji can concentrate on design and the Integral Corporation can concentrate on the business side. The design prerequisite is not to lose control over direction, even as the market by necessity may need to grow and incorporate other branded items. For example, Yohji Homme, the first men’s fragrance a mixture of cardamom, bergamot, cedar wood, leather, patchouli with a glaze of coffee was aimed at the nomadic spirit, the explorer, the adventurer, that lies dormant within every man. The fragrance references the clothes, an unchained freedom, not tied to an office, not enforced to follow the latest trend. The clothes, a veneer of freedom that we aspire to or desire and yet we are all, each of us tied to our rents, our orders and systems, confined within the cultural parameters of ones accepted social circle, entities that are difficult if not impossible to break. This freedom to reverie, the inspiration that drives us forward hoping one day to reach the escape velocity to be able to leave behind the encumbrance of conditioning and obligation. Even the sounds used at Yohji’s shows follow a consistent theme an electronic ambience for industrial landscapes of asphalt, cement and metal, scraping textures and beats of the urban landscape.

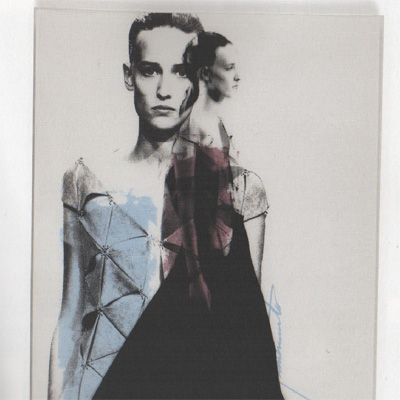

The graphics of Paul Bouden best exemplify Yohji’s work, they are themselves urban textures. The models are not the central or the total composition they are elements of a larger whole, often a scaleless composition, overlaid and transparent and always very masculine. They are rough edged, printed across the binding of a book or magazine with a very limited tonal range, graffiti, or music posters on the shuttering that surrounds building sites, temporary, passing through but with a prescience that expands, once noticed. This aesthetic spill back into Yamamoto’s later collection where image is used across clothes as if graffitied post fabrication.

Ultimately in designing clothes Yamamoto designs men’s clothes for his own taste, and women’s clothes how he believes they should be represented. He designs men’s clothes that he would like to wear, and women’s clothes that empower, clothes that describe the way he feels about the world and by sales many others feel that way too.

Images

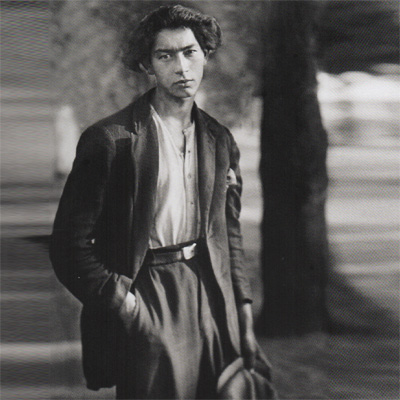

- 1. 1930c Gypsy, August Sander

- 2. YY 2004 SS, Graphics, Paul Bouden

- 3. YY 2016 AW

- 4. YY 2023 SS

- 5. YY 2021 SS

- 6. YY 2021 SS

- 7. YY 2023 SS

100822 - Grand Prix Wheel

> words

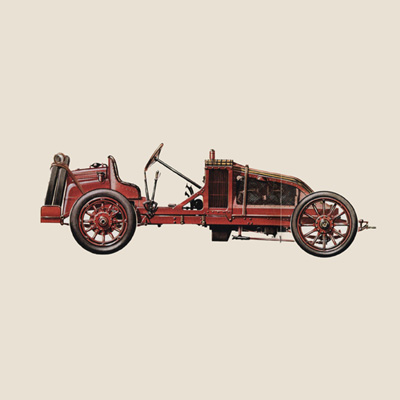

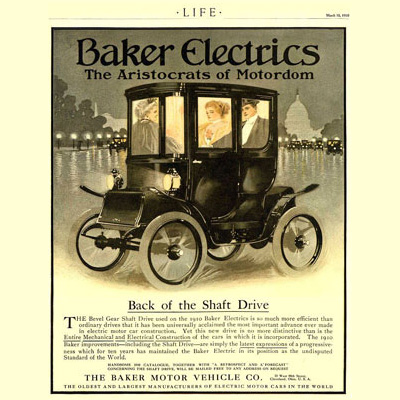

26th June 1906, the date of the first Grand Prix, Le Mans. The race was won by Ferenc Szisz in a 12.9 litre Renault (18.3 litre engines were also in the race). The car had its engine up front with its radiator fitted behind the engine, it was prop driven via the rear wheels but without the use of a differential. It had a three-speed gearbox with a leather cone clutch. The car covered 769.9 miles at an average speed of 63 mph but reached 92 mph on the straights. The Renault team used wire wheels during practice, with these the car had no wheel brakes and only engine braking to the rear wheels through the transmission. The life of a rear tyre was short. The cars had to carry both a driver and a mechanic and any repairs on the cars away from the pits were carried out by the driver and mechanic. Spare tyres were carried on the car along with the tools to fit. To fix a puncture on the track, the old tyre would be cut off by knife and a new tyre, with tube pre-inflated at low pressure was forced over the wire rim and then fully inflated, enabling the team to re-join the race. A good driver and mechanic could change a tyre in about 16 minutes. Tyre technology was in its infancy and punctures were often, meaning that a race could be won or lost on tyre changes. The Renault team had a trump card yet to be played.

The Renault Type K race car had a strong technological provenance. Of the eleven car makes taking place in the 1906 Le Mans, it was one of seven to use a shaft drive with U joints, which Renault had pioneered and had used in on all his cars from the 1898 prototype through to the Type K. It was one of six to have a three-speed gearbox, one of five to use a high-tension magneto ignition and one of two to use thermo-syphon cooling. More importantly, at the start of the race the Renault team had changed its wheels. Renault was one of the three teams running “la jante amovible”. In place of the 34x3 inch wire wheels were wooden artillery wheels. The rear wheels only incorporated a 290mm rod driven drum brake, Michelin tyres, and an eight-bolt detachable rim. With these split rim wheels it was possible to replace a tyre in under two minutes. Renault’s last-minute wheel change paid off, on the fourth lap Szisz and his mechanic changed all four wheels in 3 minutes 47 seconds, quick enough to gain a lead advantage that no other car was able to close. At the end of the first day’s racing, circa 6hrs of continuous racing, Szisz car number 3A, had a 26 minute lead.

All the cars that finished the first day’s racing were then locked in a paddock overnight in the condition that they had finished the race and they were not able to be touched. The race would recommence at staggered times the following day. This meant that Szisz would leave first and set off at 5.45am. His car, car 3A had a flat tire, Szisz drove straight to the pits, where he replaced two wheels, refilled all fluids and lubricated all joints in 11.5 minutes, still setting off 14.5 minutes before the next starter. Szisz maintained his lead throughout the day winning the first Grand Prix. His 105 h.p. side valved Renault had beaten into second place a 135 h.p. o.h.v. Fiat by a margin of 34 minutes. A race won where reliability and sensible driving, conserving tyre wear whenever possible had bettered pure power and performance. The victory bade well with Renault factory orders, the Le Mans Grand Prix race cars were adapted road cars of the day. However, why in this race was a state-of-the-art Grand prix car running on wooden spoke wheels?

The wheel was invented around 4000 BC, exact dates are unknown. This would have first been a circular wooden disc place upon an axle. The wooden disc most probably a crosscut from a tree. The spoked wooden wheel was invented around 2200 BC, it was lighter and could be used on faster moving vehicles such as chariots. The wooden spoked wheel remained in continuous use through to the 1870’s, a continuous run of over 3600 years, when it was slowly replaced by the tensioned wired spoke wheel.

The wire wheel was invented by George Cayley in 1808 but further developed and applied to bicycles by William Stanley in 1849. By the late 1800’s the wire wheel was used mainly on bicycles, tricycles and early quadricycles and yet for the 1906 Grand Prix, the Renault Type K ran on 4000-year-old wooden wheel technology. Wire wheels in 1906 were still tied radially, the shortest route from hub to rim, these wheels were not strong enough for heavy race cars driven on poor roads. Radially spoked wheels although strong in compression (they could physically hold the weight of the car) were unable to cope with momentum forces, those of acceleration and braking. When accelerating using the colossal torque of a 12.9 litre engine, the rotation forces from wheel hub to rim would collapse a radially spoked wheel. Transmission braking would have the same affect in reverse. It was not until the invention of the tangential wire wheel, designed in 1907, that a resistance to the acceleration and braking forces could be accommodated.

In 1907 John Pugh designed a tangential steel spoked wheel for Rudge-Whitworth that could safely be used on cars. These wheels owed their resistance to braking and accelerative stresses due to their two inner rows of tangential spokes. An outer row of radial spokes gave lateral strength against cornering stresses. These wheels were deeply dished so that steering pivot pins might lie as near as possible to the centreline of the tires. Their second feature was that they were easily detachable, being mounted on splined false hubs with knock-off fixings. This made changing a wheel quicker and easier. The pressed steel wheel was later invented by Joseph Sankey in 1908 and was quickly adopted by cost conscious car manufacturers. The Type K Grand Prix car had to use the technology that was available, and this meant reverting to the wooden spoke wheel.

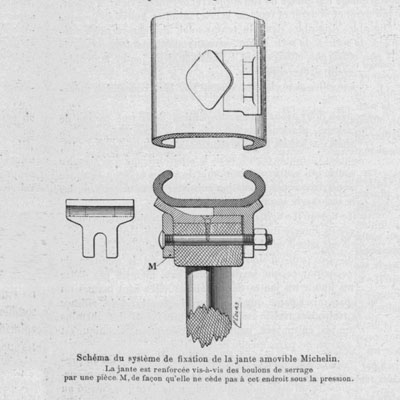

So how far could a wooden spoke G.P. race car wheel be upgraded from a wooden spoke wheel that had graced Persian chariots 4000 years prior? The Renault wooden artillery wheel had a large hub circa 240mm in diameter from which the twelve wooden spokes would radiate. The hub had a steel reinforcing plate bolted to both sides, through the wooden hub, making a steel plated sandwich and spreading torque forces over a wider circumference. Each spoke was then widened at a knuckle through which was bolted a 290 mm drum brake. The wheel and the drum brake were then one unit. The wheel then had a timber outer rim, as a conventional wooden wheel. The word tire comes from attire, as in a dressed wheel. The first tyres were a steel rim surrounding the circumference of the wheel. The steel rim would be preheated and then shrunk fit to the wheel by cooling. This provided a compression around the wheel holding it tightly together. The Renault cars had steel rims but the inner edge of the rim was turned up to support a pneumatic tyre. Around the rim were eight bolt on flanges that held the tyre in place. By undoing and removing these flanges it was possible to change a tyre without removing the wheel (see cross section detail). The technology is extremely crude, but every car related technology was still in its infancy. With early race cars design development focussed firstly on developing power from the engine, suspension, braking, roadholding would all have to wait.

Further to qualify for entry into the 1906 Grand Prix the cars had to have a maximum unladen weight of 1000kg (one metric tonne) but this is extremely misleading as to the actual weight of the car. To this weight all fluids, driver and mechanic, tools and spares would be added. These are the early days of the motorcar and there are design inefficiencies everywhere. A by-product of inefficiency is heat and with an engine as inefficient as a 1906 12.9 litre Renault the by-product is a lot of heat. To cool this heat the radiators were huge. On the earlier Renault Type K of 1903, (the car on which Marcel Renault died during the infamous 1903 Paris-Madrid race) the radiators were fixed along the full length of both outsides of the bonnet. This design inefficiency wrapped the engine in a hot water jacket making engine maintenance near impossible. The radiator was consolidated into a single unit on the 1906 Renault Type K, its sheer volume made its location a difficult problem to resolve. The radiator had an approximate volume of 1200x900x400mm and when full would have a weight of approximately 432 kgs. A radiator of that size has two pragmatic options for its location on a car, transversally mounted in front of, or behind the drivers. If mounted behind the drivers, while cooling a front engine car, its heat tubes would need to run past the driver’s, back to front of the car. Putting this much mass behind the rear axle would drastically affect handling. It was decided to put the radiator behind the engine and in front of the drivers, along the scuttle. This placed the weight central to the car but had its own issues. With the radiator behind the engine, it had almost no through ventilation and the steering column had to pass through the radiator to reach the front wheels, an insane configuration by contemporary engineering standards.

With water in this huge radiator and circulating a 12.9 litre engine, it is easy to see how quickly the car could gain additional weight on top of its unladen entry level weight of 1000kg. A 12.9 litre engine also requires a lot of oil and a car that at best returns 9 mpg requires a lot of fuel for a 700-mile race. Added to this additional weight is that of the driver, the mechanic, tools, jack and three spare wooden wheels (the rims and tyres alone weighed 18kg each). With the tank and the radiator full and the driver and mechanic on board, a 1000 kg entry car would be approaching a two tonne (2000 kg) race car. This would have been a two-tonne car capable of 100 mph, running on a dirt road with no shock absorbers, on wooden spoke wheels, with rod driven drum brakes only fitted to the rear wheels. A driver needed considerably more courage than skill to push these cars to their limits. A car without a differential would also mean that the rear wheels would need to skid round corners, as this is the only way to compensate for the difference in distance between the inner and outer radius of a bend. The huge torque of a 12.9 litre engine, with the car running on a dirt surface, the 3-inch-wide wheels would slip when accelerating or braking. This was to the benefit of the wooden wheel. A wooden wheel racing on a contemporary tarmac surface would better grip on the bends and the sheer force across the timber wheel when cornering would probably break the spokes. The slip on the 1906 Le Mans poor road surfaces made the tyres suffer but saved the wheel.

Car design was still in its early days, but competition was fierce and design development rapid. Design progress was greatly helped at first, by racing and then by mass production. Race car design in 1906 was still very crude but by the mid 1920’s cars such as the Bugatti Type 35 and the Delage 15S8 were racing with refinements recognisable today and still used on many modern cars. Racing forced designers to look at all aspects of car design, brakes, suspension, aerodynamics and to bring these design developments together into a refined whole. Ideas past swiftly from team to team and at each rejuvenation re-invented and improved. The early car designers paved the way for the millions of incremental improvements that have happened since.

Gaston Vinet was a French inventor, automobile and aviation pioneer who ran Maison G. Vinet in Courbevoie, a coachbuilding company founded in 1896. In 1900 he founded Automobiles Vinet in Neuilly-sur-Seine, which manufactured cars until 1904. He introduced the gummed wheel in France in 1893, and patented axles and brakes. His detachable rim was patented in 1905, the patent was bought by Michelin and the wheel was used on the Renault Type K that won of the 1906 GP de l'ACF. A significant win for Ferencz Szisz and Renault, but a win no less on a wooden spoked wheel.

Images

- 1. 1906 Renault Type-K.

- 2. The Gatson Vinet / Michelin Split-Rim wheel.

- 3. Gaston Vinet Split Rim patent.

- 4. Vinet / Michelin detachable rim.

- 5. A Persian Chariot wheel 2800 B.C.

- 6. Marcel Renault in the 1903 race in which he died.

- 7. Movie clips from the 1906 Grand Prix.

010822 - Model T, 1908-1927.

> words

15,007,033 is a big number, even today, but in the 1920’s it was huge, unimaginable, incomparable as it was the number of Model T cars sold between 1908 and 1927. The Model T had a greater influence than any other man-made object on the American way of life, with only the washing machine as a possible comparable, today the personal computer would also need to be considered. The cars made accessible, affordable freedom, access to travel, it opened up the roads and therefor helped urbanise, numerous businesses developed using the Model T as its primary workhorse. As a utility vehicle it was the family car, the doctor’s coupe, the builders flat back, the local fire brigade’s truck, the milk wagon, the police car and the ambulance. The Pullford Company quickly accessorized the Model T, advertising to make it a ‘Practical Tractor’ in less than 30 minutes, to be able to carry out all the work that four horses can pull. The Pullford Company offered plows, harrows, drills, mowers, hay loaders, road graders all as adaptions or add-ons to the trusty Model T. It was everyone’s ultimate utility vehicle. Famously it cost $850 dollars in 1908, its price increase to $950 dollars in 1909 but as the production numbers increased the cost came down and by 1916 a two-seater runabout would cost $345 and a four-seater touring car $360. There was no other car on the market offering as much for so little. The systematic mechanization of mass production inspired numerous copycat industries and lead to the outstanding rise of American economic growth throughout the twentieth century.

With fifteen million happy customers, it would be difficult to argue that it was a poorly designed car, but it did have some very crude details that could have easily been improved during the normal evolution of a car production life. This however was contrary to Henry Ford’s belief and aim as standardization and methods of mass production took priority when it came to design decisions. The Model T’s slow design evolution was compromised by Ford’s obsession with the ideas of inter-changeable of parts. A component from a 1908 machine would fit on a 1927 machine, and new parts could also be retro fitted. This gave the Model T great endurance and adaptability but also eventually its design became dated as other cars makes allowed the increase cost of their cars to fund the increased design development.

The Model T was not the first Ford. Henry Ford built his first experimental quadricycle in 1896 (although sometimes quoted as 1892) but commercial production did not begin until 1901. Ford built thirty cars and then his company collapsed. In 1903 Ford took a new approach and built a sprint car for use in the popular local track events, this was primarily to attract publicity, this approach succeeded and procured backers. The Ford Motor Company was then incorporated with the sum of $28,000 and production began with the Model A 1903-04. The Model A had a two-cylinder engine under the driver’s seat and a chain drive to the rear wheels. It was an expensive car at the time and did not sell well. This was followed by the unsuccessful Ford Model B, this was Ford’s first four cylinder car. Which in turn was upgraded to the Models C & F, all unsuccessful. Bowing to the pressure of his financial backers Ford produced an up market, six cylinder Model K which was equally unsuccessful. Briefly a Model N was developed but this quickly morphed into the Model T. Ford’s primary objective was always to build an affordable quality car that the man of modest means could buy and use on a daily basis. Cars at the time were very much a rich man’s toy or status symbol. In an all or nothing last attempt The Model T was developed and put into production in 1908.

Fifteen million cars sold and a huge commercial success but was the Model T a well-designed car? What was it really like to drive and own? To criticize a design, the needs to be put into context, the context of the times, the available knowledge of technologies and the available material technologies. A design also has a context of use, is it appropriate for its purpose?

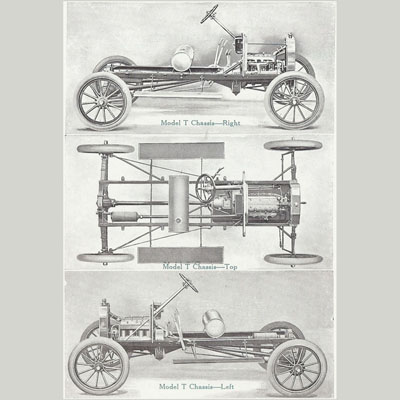

The chassis of the Model T is almost web like it is so delicate and fragile. The idea of a rigid chassis complemented with able suspension was not a design concept in the early 1900’s. The chassis consist of two thin parallel and narrowly spaced longitudinal C shaped channels with minimal cross bracing and thin radial rod diagonals to the rear axle. The track of the car was predetermined by necessity to run the cart ruts of the dirt roads. The chassis sat on transverse semi elliptical leaf springs back and front above the two axles. This gave the car a high roll centre, so it would sway or rock from side to side when on bumpy ground. The suspension, the chassis and the car body all flexed to soak up movements encountered when travelling. This would be nothing like a contemporary chassis, but it was fit for purpose, minimal and cheap to produce and could accommodate the poor roads. The flex through the chassis would eventually cause metal fatigue at all stiffening junctions and there were after-market solutions to this but in general the chassis was strong enough and appropriate for its intended use.

Henry Ford came across Vanadium steel at a racetrack on a crashed French race car. He was impressed by its strength, and weight and took a small sample for analysis and upon learning the production process he used this metal on the Model T. Vanadium steel was an advanced alloy of the time and the Model T used Vanadium steel in many places including the chassis. Vanadium steel was lighter and stronger than carbon steel, parts could be made smaller and lighter. This reduction of weight and minimalization of components, ease of assembly, access and repair were key concepts to Ford’s design philosophy. Cost was kept to a minimum by not having certain components. There was no brass, no footplates, no locks on the doors. There was no petrol pump as the tank was stored high under the seat and gravity fed to the carburettor. There was no fuel filter, any sediments fell into a bulb below the tank and could be drained. There was no water pump, water was circulated via convection, this was ok for the many open roads but not great for congested traffic, but most roads were open. There was no oil pump, the crank splashing through oil in the sump provided lubrication, a very primitive solution made worse by a very shallow sump. The gearbox used the same oil as the engine and rotated in a shallow trough of oil, the flywheel with its magneto splashing oil as it rotated. Even by using the two transverse semi elliptical springs, one per axle, saved weight, usually there would be two per axle one in each corner of the car. Running a machine that was missing all these components meant that the Ford Model T needed a lot of manual adjustments and a high level of regular maintenance.

The engine was a cast iron four-cylinder, in line, longitudinal monobloc. The engine bloc incorporated the pistons with water cooling jackets and crankshaft top mounts. A cog driven camshaft run off the crank opened inverted valves via pushrods. All of this within the cylinder bloc. The cast iron cylinder head was separate and housed only the spark plugs. A copper asbestos casket separated the head from the bloc (a Ford invention). The combustion chambers were L shaped, flat over the piston chamber and extended to overhang the valves. By contemporary standard this provided a very poor combustion chamber configuration, but this was unknown at the time. Ease of fabrication and maintenance drove design decisions. The head and block design, separated by a gasket were state of the art in 1908. Engine block and cylinder heads were often cast as one unit, also a four-cylinder monobloc incorporating water jackets was up to date engineering in 1908. Cylinders would usually be built in pairs and then paired. The aluminium sump was also separate and bolted to the bottom of the engine bloc. The Model T’s sump lacked depth, this would cause bearing problems on all cars and the crank had no counter balance and very long levers, more nodding donkey than motorcar but again this was normal for the period. The camshaft is driven off the crank and these via pushrods operate a side valve head. The engine was 2.9 litres and develop 20hp or just under 7hp per litre a deplorable inefficiency by contemporary standards but adequate for the day where inefficient 6 litre plus engines were the norm as capacity was the easiest way to create power. The crank had three main bearings and the engine had a 1243 firing order (modern car 1342). The engine, like cars of the period had a long stroke, meaning that the crankshaft has a wide radius. This gave good torque but limited the engine to around 1800rpm as the moving components were heavy. The long stroke also made the engine bloc very tall. The low rpm, high torque and light weight of the car gave it 13mpg on unrefined 40 octane fuel, a high mpg for 1908. The compression was only 4.5 to 1 allowing the engine to run on kerosene, alcohol or other poor-quality fuels of the time. The low compression also made starting by hand cranking easier, electric starters were not available as an option for the Model T until 1919 (although invented in 1903).

The whole transmission fits via a bell housing to the engine bloc, this is again contemporary, around this time gearboxes tended to be separate components attached to the engine via shafts. The Model T engine and gear box were tidy and compact unit by the standards of 1908. However, the Transmission is nothing like a contemporary gearbox. It uses elliptical planetary gears that are in constant motion as the engine turns, this drives a gearbox drive that is also in constant motion. The gears are engaged by friction collars, initially made of steel clamped cotton, operated by three pedals. Each pedal tightens a collar around a spinning pulley. The pedal on the left is pushed down and held down to engage a low forward gear, its central position is neutral (it slips), when released, top position, it engages a high forward gear. The pedal in the middle is held down to engage reverse. The pedal on the right is held down to apply a brake to the engine rotation via the transmission. Transmission braking was the norm on the early cars, most had no wheel brakes at all and only later had rear wheel brakes. There was a rear emergency brake, operated by hand and this was rod driven, its primary role was as a parking brake.

There was no battery and no dynamo, there was no high voltage distributer as in modern cars but instead four multi-spark coils firing spark plugs one per cylinder. This provided multiple sparks in the combustion chamber. There were two levers on the steering column one controlled acceleration and the other controlled ignition advance and retard. The Flywheel magneto was a simple way to generate electricity using the rotation of the flywheel as the engine turned. Magnets mounted on the flywheel move past coils mounted behind the engine this generated the electricity that fired the spark plugs. The magneto would be dropped on later post Model T Fords. The Model T was a perfect example of precision engineering of its day. A Rolls-Royce, the obvious symbol of precision and quality, was hand crafted machine with each of its parts a one off, each car bespoke. The Model T factory produced interchangeable identical parts.

“Any colour as long as its black”. The Model T’s were at first produced in many colours, eventually as production numbers increased black was the primary option as black was the fastest air drying paint, the cars stood outside to dry. Every aspect of the Model T’s design was to cut costs and produce a machine at the lowest possible price. Making the car available to a wider cliental, instead of a car only for the rich, was Henry Ford’s social mission and this determined all design decisions. The car was an amazing success and socially revolutionary. It used the best materials, up to date technologies for both car design and manufacturing, all of which were amazing achievements for 1908. Model T sales peaked at 2,011,125 units sold in 2013 and then began their decline. In total 15,007, 033 units were sold through to 1927 and approximately 60,000 still remain. Today, the Ford Model T ranks ninth in all time car sales of one production model but this today is with a global population considerably greater than in 1908. Relative to population the Ford T would still be the number one selling car.

The Model T’s main design failure was that it failed to evolve over its production period. Cars that have long production runs such as the Volkswagen Beetle, selling 21,529,464 units evolved considerable between its 1938-2003 production dates. The Model T not only failed to evolve Ford’s had no other car to offer until the Model T was taken out of production. It was replaced by the Ford Model A, 1828-1932 that sold 4.8m units during it production run. However, by then the other car makers had caught up and competition was fierce. The Great depression first hit in 1929 but by 1931 was in fall momentum, this would affect all aspects of manufacturing as survival was the prime objective for the next decade.

The Model T is a very beautiful car, it is designed as, and is recognisable as a contemporary car. It has the engine in front, shaft drive, rear differential. It has an enclosed passenger compartment, it is operated by a steering wheel, foot pedals and hand controls and yet it is still possible to see its carriage routes. The transition from horse and carriage to horseless carriage was long and complex but the early 1900’s witnessed increased speed of consolidation of design and technological development. The racetrack became the testing ground and manufacturers quickly assimilated all the best ideas into each model. The two World Wars further hastened technological development, with cross-over technologies and skills migrating across the various engineering disciplines of aircraft, weaponry, product design and car manufacture.

The Model T was Henry Ford’s most famous car. However, Henry Ford will always be best remembered for his introduction of Mass Production design and techniques to the industrial world, a system that would be copied by every other volume producer in the following decades. The production line system of high-volume mass production would not be superseded until Toyota’s Lean Design systems on the 1980’s.

Images

- 1. Model T, 1911 Runabout

- 2. Model T, Chassis

- 3. Model T, 1916 Doctors Coupe

- 4. Model T, 1911 Tourer

- 5. Model T, 1915 Town Car

- 6. Model T, 1923 ForDor Sedan

- 7. Model T, 1909 Phaeton

300320 – Van Gogh’s Shoes – The Relevance of Mis-Readings – London

> words

Pre-Amble One - Provenance and Value - The Relevance of Decoding

Pre-Amble Two – From Sportswear to Signaturewear - A Contemporary Portrait - Balenciaga Triple S Sneakers

The Critics Previous Comparatives - Van Gogh’s Shoes vs Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes

Three images of Shoes – Van Gogh, Warhol, Balenciaga

Summation

This essay looks at three images of shoes and reflects upon the societies that have produced them. The essay consists of five parts as outlined above. Three pictures of shoes, from left to right, one from 1886, one from 1980 and one from 2018. The first two images have been chosen as they have already received considerable attention, as outlined below. The third image, are a pair of shoes of today and represent aspects of today’s society. All three images represent time frames of culture, ongoing development and reappraisal.

Pre-Amble One - Provenance and Value

Provenance - The beginning of something's existence; something's origin.

Value - the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something.

Provenance, history, association, gossip, story, rumour and endorsement, are all entities that affect our perception, acceptance and eventual evaluation of something. The provenance need not physically improve or alter a product, it need not be accurate and it need not be positive to have affect. Provenance can be fickle, have considerable consequence and a two-way effect as it re-evaluates. The object that receives ‘provenance’ is re-evaluated and the giver of ‘provenance’ is equally re-evaluated.

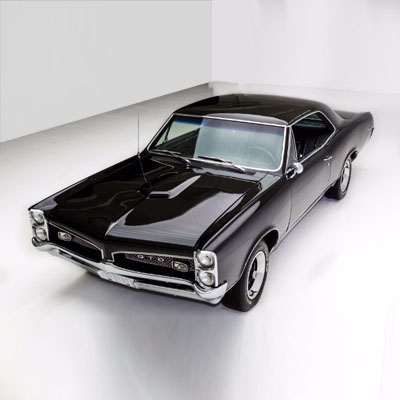

For example. A rock star is photographed sitting in a new sports car. The cars significance is increased. The rock star’s famous model boyfriend / girlfriend is photographed sitting in the passenger seat. The cars significance is increased again. The rock star is known to be a car enthusiast and has a large collection of cars. The cars significance is increased again. The rock star is known to compete in track days or amateur races. The cars significance is increased again. The rock star crashes the car. The cars significance is increased again. The rocks stars boyfriend / girlfriend is killed in the crash. The cars significance is increased again. The rock star is also killed in the crash. The cars significance is increased again. It makes little difference that the rock star may not have owned the car, that he was lent it by a famous brand as a means of endorsing their product, or that the rock star drove the car just under two miles before the fatal crash. The object that receives ‘provenance’ is re-evaluated and the giver of provenance is re-evaluated.

The above example is a fiction, but numerous examples exist. In December 1967 Elvis Presley walks into a car showroom and buys a gold 1968 Cadillac Eldorado Coupe. One morning the new Cadillac refuses to start and Elvis shoots it in the passenger side front wing, where the bullet hole still remains. In 2014 this damaged car is sold for ten times the market value of the equivalent car. Numerous examples exist of cars receiving provenance from celebrity association and of celebrities receiving provenance from their association to specific cars.

Provenance to products is transferable. Steve McQueen’s 1968 green 350 Mustang fastback, from the film Bullitt, which sold for $3.74m million in January 2020, is transferred to all 1968 green 350 Fastback Mustangs. It should be noted that Steve McQueen did not own the car but it was used by him to make the film. It should also be noted that the car sold was not the main car in the film (that was written off) but the stunt double car. Neither of these facts have altered the re-evaluation, the car via celluloid is inextricably linked to Steve Mc Queen and has been assimilated into popular culture. James Bond has done the same for Aston Martin and Lotus. Cars featured in the films Fast and Furious, Matrix or any popular film gain transferable provenance.

The above are easily accessible examples of cars, we can read about them daily, we can check prices on auction sites and numerous websites and magazines. But the same provenance / re-evaluation can be readily applied to more esoteric goods, such as Samurai swords, contemporary furniture, jewellery, fashion, architecture, memorabilia, art etc.

Artists can invent and enhance their own provenance. The Masters from the Renaissance would often include themselves as a background figure within an allegorical composition painting. This was often revealed only after the painting’s completion, sometimes not discovered until after the painter’s death. They would paint mysteries that needed to be deciphered and leave clues so that the painting could be read and more importantly endlessly re-read. The more times a story is told, enriched and embellished the more significance is added.

In Art, provenance is as, if not more important than the art itself. Provenance authenticates, it establishes the origin and hence the authenticity. This is why the art forgers first task is to convince the specialist. Eric Hebborn (1934-1996) was a struggling London painter, who purchased some paintings in a market and sold them to a gallery. The gallery put the paintings up for sale at thousands of pounds over what they had given Hebborn and he believed that the gallery had intentionally cheated him. Hebborn set out to get his revenge, at first on the art experts at the gallery and then on art experts everywhere. Hebborn painted over 1000 pictures, in a range of styles, but the Old Masters was his speciality and sold them as originals. He was wise enough not to duplicate the originals but to study them and then produce preparatory drawings for existing or ‘missing’ paintings. Many of the world’s best museums bought and showed his paintings. Once a fake had been established as authentic, it is logged and archived and the fake itself becomes a means by which authenticity of other works are judged. Hebborn was an expert in drawing, ageing and dating his works. He would provide a sketchy but well-researched history and then allow the experts to make all the connections as expert authentication adds value and re-evaluates the piece. When the forger is eventually discovered, their fame endorses their own work, and some have then set up studios creating ‘authentic’ forgeries, exact copies of famous works signed by themselves.

Contemporary artists know very well the value of provenance and create both the work and the back-story. Damien Hurst’s, ‘Treasures From The Wreck of The Unbelievable’, composed of broken, barnacled and aged sculptures are sunk off the east African coast to be discovered in 2008 and retrieved. The sculptures are supposed to be that of Cif Amotan II, a collector of antiquities, from the second century CE. The whole process of discovery and retrieval is fully documented, catalogued and filmed. The fictional back-story is in itself a piece of art as that of the sculptures themselves. In 1918 Banksy’s ‘Girl With Balloon’ is put up for sale at a Sotheby’s auction. It sells for $1.37 million. As the hammer falls on the sale, a hidden shredder inside its frame begins to shred the recently purchased painting. The painting is shredded halfway. The auctioneers look at each other in horror, but they have completely missed the cue as the painting has just considerably increased in value. It is possibly now Banksy’s most famous painting. Banksy had intended for the painting to fully shred but the shredder hidden in the frame malfunctioned and the painting was shred only halfway leaving half in the frame and the shredded half hanging from the frame. This was by far the better conclusion, exceeding the intended, as the work records and displays its own provenance.

You may ask what has any of this to do with Culture or High Art, surely this is simply market manipulation for commercial gain? The answer is Yes and No. Designed objects and works of art are records or cultural stepping stones, they document the values and beliefs from within a specific time frame. Artists and designers are windows and conduits for recording cultural history and markets are intrinsically linked to our cultural history. Democracy, globalisation and popular culture are, in the present time frame, uniquely interrelated and art and design have adjusted to this. High Art, often takes an aloof stance, but it is very much part and product of the same system that generates understanding and culture.

Pre-Amble Two – From Sportswear to Signature Wear

To make any sense of the third image some historical background information is required regarding a genre of clothing that emerged in the twentieth century. Sportswear, leisurewear and casualwear have been grouped as the same genre of clothing as they have become hybrids of each other in contemporary fashion. Sportswear entered fashion via small complimentary collections within the French high fashion houses of the 1920’s. Women started to wear looser fitting clothes and began participating in sports such as tennis, golf and swimming. Sportswear was a minor part of these collections and still often made bespoke for women of the leisure classes. However, sportswear is really America’s Post War contribution to fashion, linked to the growth of ready to wear and interchangeable separates, where it became increasingly part of the fast-paced American female wardrobe. American sportswear was seen as an expression of middle-class values, including comfort, function, health and the concept of democracy. The established eight-hour day, five day working week enabled a growth in leisure time for all classes and clothing was required to embrace this new found freedom. Advertisements for women began to embrace the ‘American look’ of good health, good teeth, good grooming, fit and free. American sportswear designers focused on mass produced, affordable, versatile, easy wear garments. While the post war Paris fashion houses imposed their styles on their wealthy clients, American sportswear was widely available, encouraged self-expression, and accessible to all and as such, seen to be democratic. During the 1970’s Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein and Perry Ellis produced sportswear made in natural fibres, brushed cotton, wool mixes and linen. By the late 1970’s American designers were producing extremely simple garments in high quality fabrics that have become modern classics and these have barely changed over the years. Casual had become minimal, with simple clean cuts. These fashions were endorsed on a global stage by America’s command of film and music, through these mediums they expressed new youthful freedoms, new independent ways to live, the all-American lifestyle.

As the lines between sports and casual wear became blurred and mixed, the music of the 1980’s and 1990’s opened new possibilities for this type of apparel. Popular culture saw the music of the 60’s and 70’s as a visual spectator-based recreation. The music of the 80’s and 90’s was far more activity based and dance orientated and this evolved a clothing style appropriate for the new genres. At the same time global access to TV had popularised sports at a domestic and international level. Teams with their colours, hierarchal uniforms and brand association gained a popular following among fans. Popular culture and business were inseparable as money follows and manipulates the markets. Street fashion, from necessity, has to be inventive on a budget. Mixing second hand separates and casuals with sportswear was an easy and practical step, layering all of these into a new streetwear most recognisable through the Hip-Hop scenes of the 80’s and 90’s who often wore the uniforms of one brand, adidas, Nike etc. Further into this mix came other forms of street culture as leisure time amongst the young increased. Skateboards, Surfing, BMX, B-Boys all had their own dress codes. Leisure became increasingly activity based or at least one could dress with the resemblance of association to an activity lifestyle. Clothes became tribal through association but tribal within a global catchment of popular genres. Mass markets had huge financial potentials and the big brands followed this. Soon the alternative became mainstream, break-dancing, surfing, BMX, became international sponsored events and ambassadors from within the scenes were courted by brands and able to earn considerable incomes. Brand Ambassadors and Influencers could be seen in the front rows at the catwalks of high fashion.

High fashion had to reinvent itself to follow the markets. Couture, bespoke and quality were replaced with the creation of ‘Difference’. Signature clothes replaced tailored clothes, from Generation X (1961) onwards, the youth market, that may have baulked at spending $800 on a new suit, would gladly spend that on the correctly tagged t-shirts or trainers. ‘Difference’ through fast turnover, limited availability and immediate association became the call of the Instagram society. Flags were worn, Brands brandished, Tags noted, all signifiers of association to a particular lifestyle and attitude to life. When brands such as Gucci adopt the mix of street fashions and place multi thousand-dollar price tags on them, this appropriation is self-reinforcing. Drawing from popular culture and directly feeding into popular culture enables the media to manipulate and create new markets. Demna Gvasalia, the creative director of Balenciaga, explains how luxury products have changed. “The emphasis has gone from quality and craftsmanship into the uniqueness of the product, A high price tag isn’t the only way to ensure scarcity. Streetwear brands have pioneered a strategy called “the drop,” where they let new products trickle into stores in small quantities on a regular basis, scarcity has fuelled a massive secondary market” The role of music and the fictive alternate lifestyles developed within club culture should not be underestimated. In the US alone Hip-Hop has the largest following of the music genres, at around 25% of total market sales, it is now a multi-billion-dollar industry. Product endorsements and limited-edition signature ranges have made many Hip-Hop celebrities incredibly wealthy and with their wealth and fame their endorsement value grows. Rappers are no longer just Rappers but instead company CEO’s, designers, actors and market influencers. The web has helped enforce and aid the growth of this mix.

High fashion has adapted, it no longer takes an aloof stance but instead is more a mirror of society. Street fashion with its influences from sportswear, clubwear, gaming and anime is absorbed by the fashion house, deconstructed, re-worked, re-composed, styled with an exaggerated edge. The material technicity of sportswear, 3D fabric forming, moulding, bonding, makes the whole look progressive and futuristic. This is intrinsically linked to digital communication, film stingers, sound-bites, hyper-real and interactive graphics, all of which help create these super-intense aspirational worlds created within ads. Instant digital media is a condensed experience, a thick syrup of real life, delivered in a few mega-bites of data and as such, an inaccessible simulacra, a hyper-real simulation of a reality that never existed. This offering of the unobtainable can be purchased through symbolic association and this symbolic association has a greater value in today’s society than the traditional quality and craft of making that would have been associated with previous fashions.

The wealthy are able to live in a multi-stratified world above the everyday. Here, they inhabit a world based upon choice, to either live inside or outside reality whenever the occasion requires. The majority of the population have little choice when directing their own lives, and respond daily to circumstance. Most can barely keep up with the cost of reality, they can hardly afford their cities, the major part of their life consumed by the cost of existence. The repetitious banality of the everyday is endured through the escape into fictive realms. These would once have been those of the story teller or the novel, today, its first point of call is TV and the internet, its second is music and club culture and its third would be the packaged tour or themed event. In these realms hope, optimism, group acceptance and personal success are superficially achievable in this digitised or themed, socially mobile, the American Dream. Where once the t-shirt, as signifier was the substitute for one’s own reality, today we have avatars, online identities, photoshopped ideal personas complete with imaginary CV’s. Reality has no place in these fictive worlds. Optimism, hope and moral justice, once the realm of the religious parable or folklore fairy tales are now part of everyday popular culture. In these fictive worlds super heroes abound. Those fictive super heroes that have been lucky enough to have mutated, have developed super powers and dress accordingly. They inhabit our gaming culture and our action films. These fictive worlds feed back into reality, through role play, fandom, adoption of gesture and mannerisms, clothing and merchandising. Manga films inspire Cosplay and Harajuku cultures that fill clubland and overspill into our urban environments. The fashion world mirrors this and gives it a more credible edge and makes it available to the mass markets.

Just as Warhol commodified celebrities through image, here activity and myth have been commodified. For the very few that dedicate their lives to pushing the limits of their alternative arts, be it BMX, Skateboarding or B-Boying etc. the majority are satisfied with association through tags. It requires no skill to wear a t-shirt, grow a beard or adorn a tattoo but all of these signifiers carry a disproportionate significance with regard to the owner’s personal achievements. The skilled individual has been outcast, he/she has been replaced by this new tag enhanced collective popular culture that gains strength from unity and identity and this group identity can be commodified.

The Critics Previous Comparatives

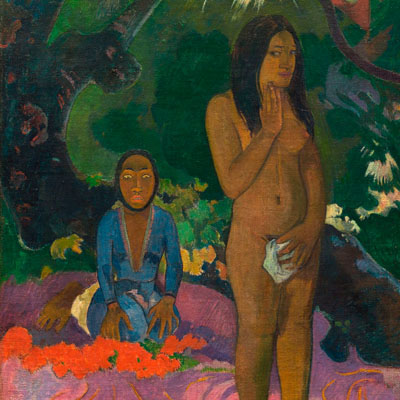

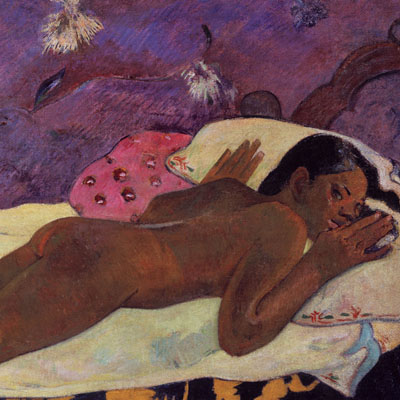

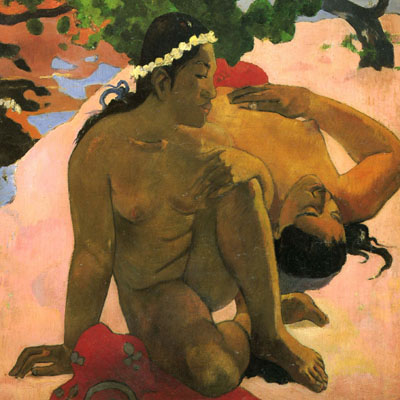

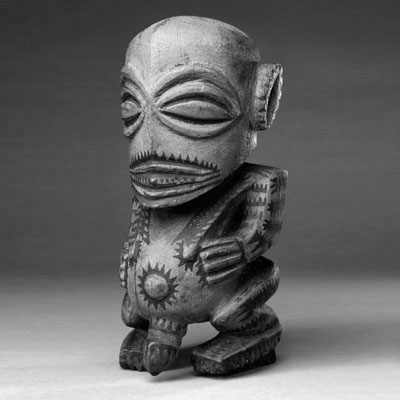

Above we are presented with three images, two of these have gained in notoriety due to receiving considerable critical attention and have from this had to be re-assessed and re-evaluated. The two paintings, both simple paintings of shoes, have been the subject of much discussion with regard to both the interpretation and role of Art within society and culture. The paintings are Van Gogh’s Shoes and Andy Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes. What has previously been said about these two pictures needs to be outlined to be contextualised. These images of course, were not chosen at random, they are images more famous for the critic’s discussions around their meaning than as artisan exercises in the representation of a still life. So, it would seem appropriate, to start at the beginning with that controversial paragraph, written eighty-five years ago, that set all this dialogue in motion

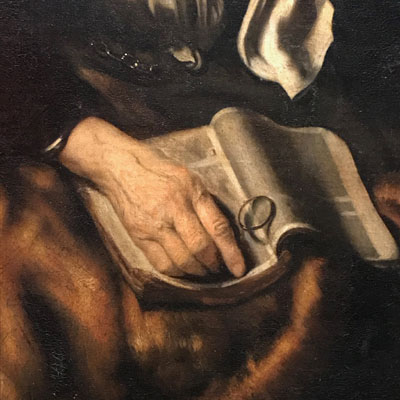

“From the dark opening of the worn insides of the shoes the toilsome tread of the worker stares forth. In the stiffly rugged heaviness of the shoes there is the accumulated tenacity of her slow trudge through the far-spreading and ever-uniform furrows of the field swept by a raw wind. On the leather lie the dampness and richness of the soil. Under the soles slides the loneliness of the field-path as evening falls. In the shoes vibrates the silent call of the earth, its quiet gift of the ripening grain and its unexplained self-refusal in the fallow desolation of the wintry field. This equipment is pervaded by uncomplaining anxiety as to the certainty of bread, the wordless joy of having once more withstood want, the trembling before the impending childbed and shivering at the surrounding menace of death. This equipment belongs to the earth, and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman. From out of this protected belonging the equipment itself rises to its resting-within-itself.”

In this quote from ‘The Origin of a Work of Art’, 1935, Martin Heidegger, the wordsmith, does what he does best and offers a worthy phenomenological description. Heidegger’s text trembles overwhelmed by his individual interpretation of this painting in which he puts emphasis upon the owner of the shoes as a means of interpreting the painting. Heidegger also puts emphasis on societies need to understand a painting by reading into the subject the personal context. Here he portrays the shoes as that of a peasant woman and he reads the painting as representative of her personal struggle to survive the harsh realities of life. Heidegger’s text is focussed around the assumption that these shoes are that of a peasant woman, unfortunately this assumption is almost certainly flawed.

In ‘The Still Life as a Personal Object’, 1968, Meyer Schapiro criticises Heidegger and re-writes the painting in his own image, replacing the peasant woman as the owner of the shoes with the shoes being Van Gogh’s own. Schapiro sees the painting as a self-portrait by the artist to represent his life’s struggle for acceptance and artistic recognition. This reading is probably more accurate as we know from Gauguin that Van Gogh painted several paintings of his own shoes.

In ‘The Truth in Painting’, 1976, Jacques Derrida picks up the baton and both critics are hit again, this time with the lengthy polyphonic virtuosity of Derrida’s endless semantic riddles. At one point during his text he invites the reader, to read, in full, the original Heidegger text in both German and then in both French and English translations. He questions assumptions made by both Heidegger and Schapiro around the ideas of ownership and if the shoes are even a pair. Derrida finds fault in the two previous critiques but offers little in the way of a reading.

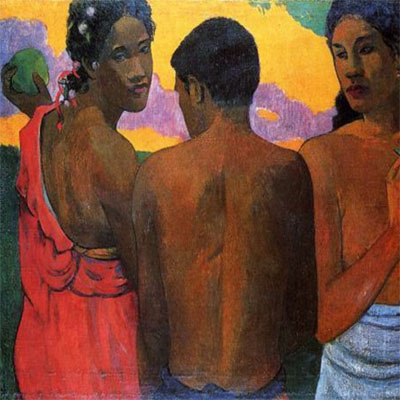

Frederic Jameson picks this up yet again in ‘Postmodernism or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism’ 1984, and compares two readings of the Van Gogh’s shoes and agrees with the possibility of each. He then adds as a comparative Andy Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes. (Although both the Van Gogh’s painting of boots and Warhol’s painting of shoes referenced by Jameson (p10a&b) are both incorrect images). Jameson suggests that the methods of reading the Modern, Van Gogh painting, cannot be applied to the Warhol Postmodern painting and his interest is in why these previous methods of art interpretation are now inappropriate.

The Van Gogh shoes high claim to fame comes not directly from the painting or the painter, but from the attention the painting received from critics and writers. This single pair of shoes, on a yellow background, was to become fuel for philosophers as they questioned arts role, its meaning and how it is perceived and interpreted. To make any sense of these texts one has to put them in the context of the critic. Each of these essays shifts the focus of content from the painting to the content of the previous criticism. They are conversations in time and are important as they reveal as much about the context and time in which they were written as they do about the original painting. Equally important is how that written context is viewed in the present. The essays show how perception changes with time and context and how societies develop within the flux of constant self-reappraisal. So, now let us try to contextualise the paintings and the critiques of the paintings beginning with Van Gogh, the original author and the following chronological sequence of critiques. Contrary to Derrida, to be able to offer any reading one needs to begin with educated assumptions. These assumptions are of course made from within this present time frame and as with the previous readings this context is in a constant state of flux but a snapshot time frame is required and is very much a component of that flux.

The source of the shoes will always be inconclusive, two personal variants exist. One is that Van Gogh bought a pair of old working boots from a Paris flee market in 1886 and took them back to his studio in the Montmartre district of Paris. It is known that he tried to wear them but they did not fit so instead he used them as a subject for a painting. Gaugin however offers another slightly more credible story. Having lived with Van Gogh in Arles in 1888. Gaugin asks him about the painting of the shoes, by this time there would be several paintings of shoes that had been made between 1886-88. Van Gogh replies “My father,” he said, “was a pastor, and at his urging I pursued theological studies in order to prepare for my future vocation. As a young pastor I left for Belgium one fine morning without telling my family to preach the gospel in the factories, not as I had been taught but as I understood it myself. These shoes, as you see, have bravely endured the fatigue of that trip.” If this story is to be believed, then for Van Gogh the shoes were a memorable piece of his own life, a sacred relic. The shoes represent the essence of himself, a homage of his struggle to share his beliefs. Van Gogh sees beauty in honesty and simplicity. However, the shoes paintings may simple have been experiments in paint and render. Impressionism, including Van Gogh’s own Impressionism was being invented on the run, canvas by canvas. The meaning of this non allegorical painting is a subconscious sensorial transference, a feeling about oneself and the time in which one lives.

Famously Van Gogh only sold one painting during his lifetime, as a struggling artist models were beyond his means, he had no clients or patrons, his paintings were unwanted. He was working at a time of great industrial disruption in both the cities and countryside, where mechanisation had replaced manual labour, the mechanical camera now captured realism better than the artist could. Impressionists sort to capture feeling and mood, tinged with nostalgia for a fast disappearing rural idyll. Industrialisation is a great gatherer and accumulator, bringing together collective labour, previously widespread resources, dispersed capital funding, all are focused to serve the machine and its products. An alienating overview, heartfelt, if not fully perceived at the time of Van Gogh. The Impressionists were part of a collective reaction to these times and a conduit for this reaction. Van Gogh’s shoe painting, torn between struggle verses optimism, represent a generic portrait of the common man, weathered and beaten, set against a background of ochre, Van Gogh’s ‘Happy Yellow’.

Heidegger’s text comes from an entirely different context, that of the established academic. Heidegger came across Van Gogh’s shoe painting at an exhibition in Amsterdam in 1930, forty-six years after the shoes were painted. Van Gogh’s work had now transcended from unwanted to collectable, its social status and influence increased by its new found financial value. Impressionism is no longer the art world’s young antagonist upstart but is now a respected and acknowledged historical Art movement of which Van Gogh was part. His life as a struggling artist, his bouts of insanity linked to chronic depression and his eventual suicide all add to his works provenance. In 1930 Heidegger is an established intellectual and academic, his Being and Time was published 1927 and was well received and highly influential. 1930 sits in the midst of two World Wars of which Heidegger had already served in WWI. Germany is in the midst of an identity crisis; post WWI hyper-inflation had desolated the country. The industrial Ruhr valley was controlled by France. Germany seeks unity and stability through Nationalism and Fascism is endemic. Heidegger, by 1933, was a full member of the Nazi Party.

Heidegger saw art as not merely the representation of the way things are but as a product of society’s shared understanding. For him, every time a new artwork was added to a culture, the meaning of what it is to exist is inherently changed as art is a form of reappraisal. The artist is not in control of the artwork, art itself, a product of culture, becomes a force that uses the artist for its own purpose. Art must therefore be considered in the context and time of its creation. The artwork is about the painter who painted it, how it was painted, the subject and its context. In Van Gogh’s painting, this is the owner and maker of the boots. Art by its very nature is not a scientific text, readings are interpretations that in themselves become minor artworks. The psychoanalytical works of Sigmund Freud were influential and well-read among academics, the sub-conscious, free association and transference were central to the analytical process. Van Gogh’s ongoing battle with depression and his eventual suicide would be irresistible to Freudian methods of analysis. All of this would put emphasis on the place of the individual within society. Heidegger takes an aloof stance, looking down on the his assumed owner of the shoes, the peasant woman, as a fraught lone individual.

The opening quote of this essay, is Heidegger’s elaboration, his interpretation from the perspective of Heidegger, a German intellectual, written a generation away from the painting’s original conception. Much has been written of Heidegger’s search for ‘the meaning of things’, his work has been extremely influential among the Existentialists. The search for meaning in a world ripped apart by the chaos of World Wars, where mankind’s devoted and constructive energy is put towards the building of machines of mass destruction, would seem an essential existential need. Hyper-inflation and commercial fiscal instability, would further query the reality of the everyday and its meaning and purpose. Heidegger’s phenomenological reading may be a fanciful over-reading of an image but his methodology is considered and has become an incorporated method of art criticism. However, ‘meaning’ read into paintings, as phenomenological description, contextualise a cultures perspective upon a subject (the shoe painting) within Heidegger’s time frame. This critic and painting are then viewed from the cultural perspective of the present. This continued reaffirmation is the means by which collective knowledge is accumulated dispersed and reinvented.

For Meyer Schapiro, an art historian as opposed to Heidegger the philosopher, shifts the context again. In ‘The Still Life as a Personal Object’, 1968. Schapiro sees Van Gogh’s shoes as a self-portrait without the artist being present. In isolating his own old, well-worn shoes on a canvas, he turns them to the audience. Shoes bear all the burden of struggle, age and fatigue, they stain with time, crack with age and wear out from the pressure and heaviness of one’s daily mobile tasks. They mark the owner’s station in life, his predicament, his inescapable position in society. In the painting of the shoes, the artist, Van Gogh stands naked but invisible. Schapiro’s reading is from the context of post WWII America. Fascist Nationalism has been set aside and replaced by Marxist Socialism, here the individuals voice and the individuals struggle have value and Schapiro concludes the painting to be a self-portrait. Schapiro had considerable knowledge of European history and the historical context in which paintings were produced, his first book in 1950 was on Van Gogh.

In 1978, Jacques Derrida returns to the subject of Van Gogh’s shoes in ‘The Truth in Painting’. Derrida’s Deconstructive stance is in line with Postmodernists rejection of metanarratives and universal truths. He concentrates on the dialogue between Heidegger and Schapiro and deconstructs each case by emphasising that there are no truths to the assumptions made within each text. He puts emphasis on the assumption of ownership, whose shoes are they, but also on the assumption that the shoes are a pair. Derrida reads through the critiques and builds an attorney’s case, questioning every assumption made by the previous critics about the painting. Often this can be an exercise in grammatology or the precise meaning of individual words. The original painting becomes a background subject and the dialogue around the subject has precedence. Although many of the points mentioned by Derrida have relevance, assumptions need to be made to offer a reading or to even begin a constructive conversation. Derrida’s text comes from a period of cultural self-questioning. The Modern Movement, with its universal reductive rules, had been seen by many to have failed, Postmodernism offered a new plurality but not necessarily a direction, it offered a means of re-evaluation but not a conclusion, as a conclusion would be just another metanarrative, an imposed truth. Derrida’s text is written in the first person, as if it is a conversation about possibilities and interpretations. It is set without the forming ground of opinion, it assumes that the basis of critical opinion has plurality and is always in flux, the Postmodern age being a time of incessant choosing. Van Gogh’s shoes were composed by Van Gogh within his time frame and context. Criticism of Van Gogh’s shoes are equally composed within their own time frame and context. The flux associated with the readings come from the passage of time and not from the moment in time.

Jameson suggests that these hermeneutic readings of the Van Gogh’s painting are possible as the work has imbued depth, as its author has considered each brush stroke, controlled its direction and texture, selected the tonal range of the colour pallet, arranged and rearranged the composition and chosen the framing and the juxtaposition of background. The author has filled the canvas with feeling, his persona and his temperament. Jameson sees the van Gogh work as an inert object form and should be read as evidence of some vaster reality which replaces it as its ultimate truth.

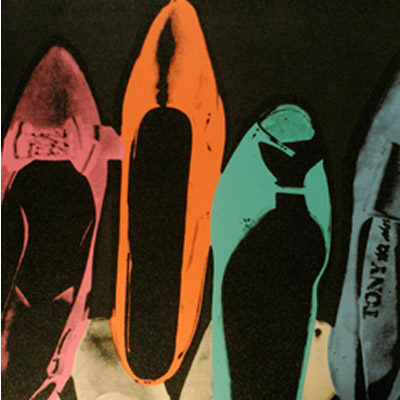

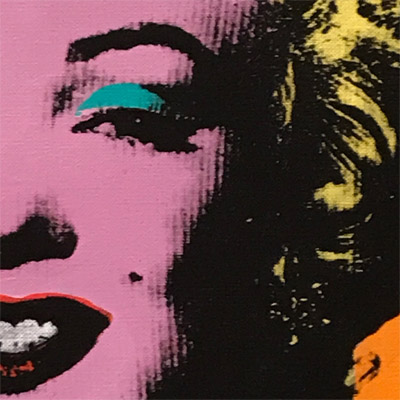

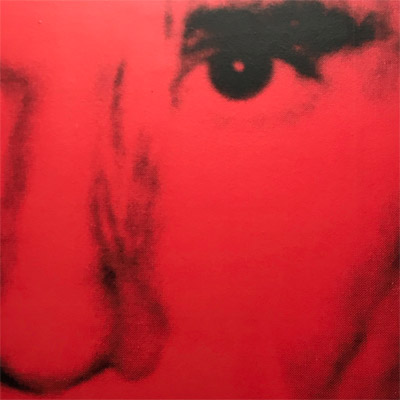

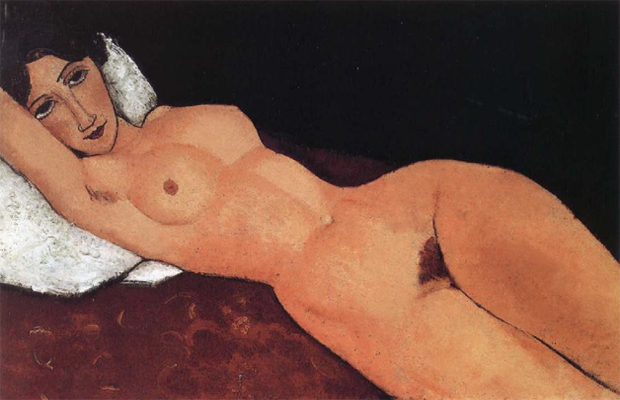

Jameson goes on to compare Van Gogh’s shoes with Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes, however, compared to the Warhol painting, already flattened twice, through the mechanical process of reproduction, photograph and the silk screen, this image is a simulacra that cannot be read in the same way or contain the same depth of meaning as the Modern Van Gogh painting. Frederic suggests that the Warhol shoes are distant, and cannot contain the intimacy of the Van Gogh shoes and that the Diamond Dust Shoes histories are unable to be identified. Instead we have a random collection of dead objects that we are unable to restore to a larger lived context. Warhol through the commodification of objects transfers its subjects, even celebrity human subjects such as Marilyn Monroe, into commodities of their own image. To surmise Frederic the Van Gogh’s painting is grounded in its materiality, the material of paint and canvass, the materials of the shoes and the shoes use by people. The Warhol shoes lack materiality as they have been moved into the world of exchange value, of surfaces and play, a simulation, a copy for which there is no original.

Three images of Shoes

What is the relevance of these essays with regard to Culture and their Cultural contribution? Are they too esoteric to have any purpose or meaning? When isolated as individual essays they are indeed sole critiques of the subject but when considered as a collective their interpretations re-evaluate societies values and direction. Heidegger, Schapiro and Derrida, when they are not disseminating each-others text focus on who the shoes belong to and from that context a precis can be formed. Van Gogh painted six paintings of old shoes and in every painting the shoes are isolated. Of these six, the painting above is the picture of prime relevance to the art world. The six paintings are still life’s and exercises in technique, Van Gogh painted because he enjoyed painting, it allowed him to cope with life. The shoes may have all been his or may not. The value of the shoe painting pictured is not of the individual but of the historic period that it represents. Heidegger’s contextual reading of the painting, as methodology, is important but subjective over reading into the personal misses the paintings historic relevance. Schapiro’s criticism of Heidegger challenges the shoe ownership and describes the painting as a Van Gogh self-portrait, without the artist being present. Derrida takes both Heidegger’s and Schapiro’s texts as being heavily flawed, and like a prosecution attorney lists faults in each case. He pulls the critiques apart but then leaves the pieces on the table, as a Postmodern critic, he refuses to conclude by inferring an alternative metanarrative. Jameson looks at the methodologies used in the formation of the previous critiques and argues that the same methods cannot be used to assess contemporary art as contemporary art has been stripped of imbued meaning. The Warhol painting has been distanced from the observer by the mechanisation of its production and by the mechanised production of its subject shoes, both shoe and painting are exchange value commodities.

It is worth looking at these two paintings again from the present perspective to form an assessment outside of the previous critiques and to add to these a new image of a contemporary shoe. Three images of shoes spanning 132 years of time, in which societies relationship to each shoe, its purpose and meaning has undergone considerable change, as societies and their values have changed.

In 1886 the Van Gogh shoes would have been made by hand, they took time to make, they were organic, made of life, they are embedded with sacrifice both in their procurement and in their use. They age as natural materials age, crease and crack, weather as skin. The shoes would be expensive items to buy, saved up for over time and yet an essential necessity, a survival item. The owner would look after them, repair them, they are intended to have longevity. With time and wear they become more like the owner. The relationship to the object becomes one of shared experience and stops being one of possession. The painting can be read as a portrait of the generic working man set within a time frame of great transition. After the invention of the camera, Van Gogh like all impressionists was searching for a means of emotive representation and this involved experiments in technique. The Impressionists had a nostalgia for the past as a rooted reaction to the uncertainty of the future. In the shoe painting Van Gogh frames the canvass. The shoes face forwards, confronting the audience. Frontal, questioning, laces undone, step into my shoes? The shoes are painted in isolation on a background that sets mood but is non descriptive or revealing. The background is mainly of yellows and ochres, to Van Gogh, optimistic happy colours. He famously once ate yellow paint in an attempt to become happy. The framing is static, not quite square but of the proportion that puts the subject in the position of centre focus. All of these attributes are techniques of portraiture. The shoes are presented as a portrait but not necessarily of an individual but instead of a displaced generation in turmoil. A generation in which all precedents are questioned, religion due to science, craft due to mechanisation, displacement due to industrialisation, meaning, value and authenticity due to mechanical reproduction. For a generation, all these values that were once solid are now transitory, in the process of great change and/or slowly disappearing. This test of inherent values and man’s displacement has been represented by the portrait of the invisible generic owner of these shoes. These personal, valuable, essential utilities.

Numerous versions of Andy Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoe’s, like the Van Gogh’s shoes, exist. Warhol, when working as a commercial illustrator for the fashion industry first created his Diamond Dust Shoes in 1950. These have probably been retrospectively titled as Warhol did not come across the technique of adding Diamond Dust to a screen print until 1979. Warhol revisits the shoe subject in the 1980’s again for a commercial ad-campaign for the fashion designer Roy Halston Frowick (Halston). A large box of Halston shoes arrived at Warhol’s studio where Ronnie Cultrone, Warhol’s assistant, tipped them onto the floor, Warhol liked the way the spontaneous arrangement looked and took Polaroids. The Polaroid was the favoured medium of Warhol’s for recording image, it was quick, immediate, its colours poster like and acidic and it was disposable, an instant gift. Warhol would choose a Polaroid image to be sent to the lab and enlarged, turned into a monochrome screen print, to which Warhol would then add further colour. Diamond Dust was then added to the surface of the screen print. Diamond Dust is a ground glitter from a natural crystal, although Warhol preferred to use ground glass. Glass a low-cost commercial product, is used to create literal glamour, a mass-produced material used to create the illusion of wealth. The Diamond Dust addition gives an appropriate shimmer, a reflection of mirror ball glitz and the disco lamé of Studio 54 and of 1980’s New York.